Idlewild, Michigan

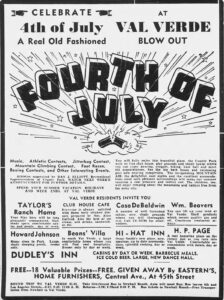

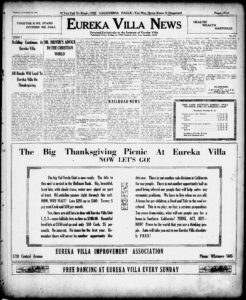

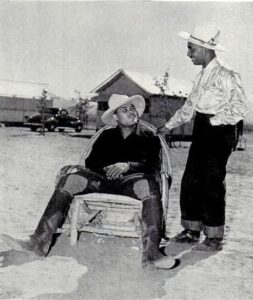

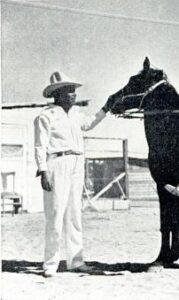

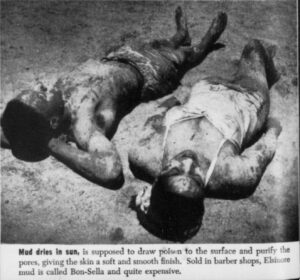

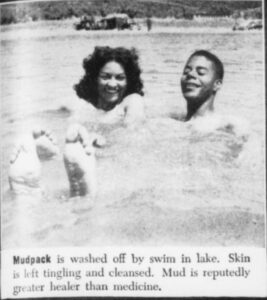

Known as “the Black Eden ” or the “wild place” in the woods, Idlewild resort was a safe haven founded in 1912 by white land developers that turned into a prominent African American community in the west side of Michigan. To get away from discrimination and the brutality of Jim Crow, Idlewild catered to multiple classes of Black folks, becoming famous for its nightlife, Black-owned businesses, and moments of stillness that welcomed tranquility, childlike wonder, and peaceful memories to anyone who vacationed there. Offering an array of options for leisure such as beautiful lakes of pure spring water, views of sparkling streams, a surplus of fish in healthy waters, skating rinks, beauty shops, hotels, cabins, profusions of flowers and berries to be collected, and a booming nightlife, Idlewild was the ideal Black summer spot. Idlewild allowed African Americans to remove themselves from cities, consumerism, and socioeconomic hardship of the time to enjoy the restorative qualities that the resort had to offer.

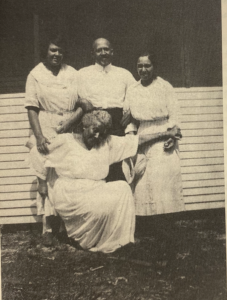

Idlewild caught the attention of many Black historical figures who decided to buy property because of its importance to the Black community. Patrons such as Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, who was one of the first surgeons ever to perform a successful operation on the human heart, purchased land in Idlewild. A small cabin overlooking Idlewild Lake and a hotel both named Oakmere, “a place of sacred memories,” became known as one of many restful spots at the resort. Idlewild vacationers left the resort inspired, so much so that a winning essay by visitor H.H. Thweatt encouraged W.E.B. Du Bois to visit Idlewild in 1921 and buy nine plots. Du Bois helped propel the resort into the national spotlight, publically noting Idlewild, “For sheer physical beauty- for sheen of water and golden air, for nobleness of tree and flower of shrub, for shining river and song of bird and the low, moving whisper of the sun, moon, and star; it is the beautifulest stretch I have seen for twenty years.” Black feminists at the time vacationed and owned their own land at the resort as business and civic leaders, educators, and activists, demonstrating Black women’s influence in the twentieth century. Violette Neatley Anderson, Irene McCoy Gaines, and Madam C.J. Walker, among others, have demonstrated how the women of Idlewild significantly contributed to the development of Idlewild’s entirely Black resort community, and to the overall elevation of their race.

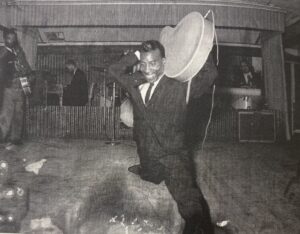

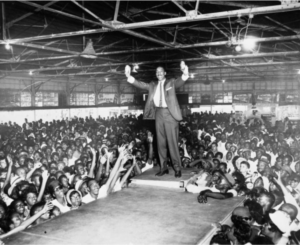

Idlewild’s Clubhouse and nightclubs played host to renowned Black entertainers of the era, such as Aretha Franklin, The Temptations, and B.B. King. Notable figures like Lillian and Louis Armstrong even chose to spend their weekends vacationing there, alongside a myriad of other esteemed artists. Idlewild was a vibrant hub, a place where diverse individuals crossed paths or established deep roots within the community. However, the passing of the Civil Rights Act heralded the onset of challenging times for Idlewild. Losing visitors that started to branch out, Idlewild struggled economically, becoming stuck in time. Despite past challenges, Idlewild continues to embody a rich history. Reimagined in 2003 as a historical retreat for the Black community, it stands as a beacon of restorative history for all visitors, symbolizing rest and leisure as forms of resistance. Renovations of the resort have been made to continue its legacy educating younger generations of the resorts cultural and social importance in America. The resort can still be visited today and continues to hold the importance of Black history and pride.

1Armstead, Myra B. Young. “Revisiting Hotels and Other Lodgings: American Tourist Spaces through the Lens of Black Pleasure-Travelers, 1880-1950.” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 25 (2005): 136–59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40007722?searchText=Idlewild+black+owned+businesses&search

Myra B. Young Armstead. “Revisiting Hotels and Other Lodgings: American Tourist Spaces through the Lenses of Black Pleasure-Travelers, 1880-1950” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 25 (2005). pg 149.

Yale University Library Digital Collections, “Genuine Photographs –Idlewild Michigan”, https://library.yale.edu/

Detroit Public Library: Digital Collections, “View of man rowing a boat on the lake at the Idlewild resort community in Idlewild, Michigan” (1950). https://digitalcollections.detroitpubliclibrary.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A249547

Yale University Library Digital Collections, “Map of Idlewild, Lake Co., Mich”, (1912-1920) https://library.yale.edu/

Stephens, Ronald J. Idlewild: The Rise, Decline, and Rebirth of a Unique African American Resort Town. University of Michigan Press, 2013.

W.E.B. DuBois, “Modernist Journals: Crisis. A Record of the Darker Races. Vol. 14, No. 4,” Modernist Journals | Crisis. A Record of the Darker Races. Vol. 14, No. 4, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510732/#, pgs 9-10.

List of Images

- Cover photo- “Snapshot of vacationers at beach” https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16864576?child_oid=16864590

- Original map photo- Yale University Library Digital Collections, “Genuine Photographs –Idlewild Michigan”, https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/17390840?child_oid=17390842

- Map thumbnail- Yale University Library Digital Collections, “Fiesta Room in Paradise, Idlewild Magazine” https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16531820

- Map Thumbnail- “The Club Paradise Garden Idlewild,” Postcard. Jones, Lindsay, Nelson, and Lynch families papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Mich”https://libraries.emory.edu/rose/collections/emory-university-archives

- Map Thumbnail- Hart, John Fraser. “A Rural Retreat for Northern Negroes.” Geographical Review 50, no. 2 (1960): pg 157. https://www.jstor.org/stable/211505?searchText=Idlewild+black+owned+businessesq=9

- Map Thumbnail- “Idlewild Historical Marker.” Historical Marker, September 29, 2021. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=182804.

Map thumbnail photos descriptions can be found at the bottom of the page

Many musicians were seen performing at Idlewild that influenced rhythm and blues, West Coast blues, and the jazz scene such as Brook Benton, T-Bone Walker, Jackie Wilson, and Della Reese.

“Like two playful children, my wife and I roamed the cultivated fields, rambled through the woods, drank the healthful turpentine water that collected in the boxes of the pine trees, picked blackberries, waded streams, till we found our cheeks glowing with the hot blood of youthful vigor and our limbs full of childish activity.”style=”color:white; text-decoration:underline;” – H.H. Thweatt “The Best Summer I Ever Spent”