Highland Beach, Maryland

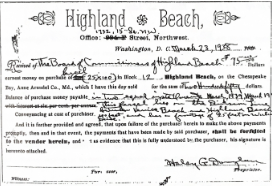

Highland Beach, Maryland, was an exclusively Black elite community established in 1892 by Charles and Laura Douglass in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Unfolding the story of Charles Douglass’ purchase, the Douglass couple was denied service at the B&O Resort in Annapolis, and after leaving the establishment, they walked down a creek and over a bridge with a view of the Chesapeake Bay. Along the way, they came across a farmer named Brashears, who owned the property and wanted to sell the land due to insufficient land for his crops. Charles Douglass viewed the acquisition of the forty-acre parcel of land as a venture fraught with risk. He made a $1,000 investment in the property and then transferred ownership to his son Joseph to avoid any potential conflict with his duty as a Federal Civil Servant.

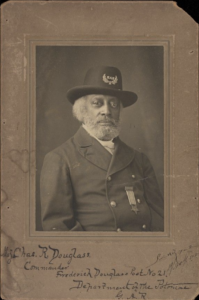

Charles Douglass immediately got to work. He subdivided the land into 131 lots the size of 50 by 150 feet and created avenues named after Frederick Douglass, John Mercer Langston, Blanche K. Bruce, John R. Lynch, Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback, and Rev. Alexander Walker Wayman–all prominent Black historical figures. The first house to be built was Charles Douglass’ in 1894, followed by the “Twin Oaks” house for his father, Frederick Douglass, in 1895. Subsequently, Highland Beach attracted a number of Black elites, with some who even purchased properties there, including Mary Church Terrell, George T. Bowen, and Dr. John Francis.

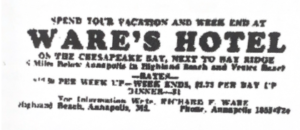

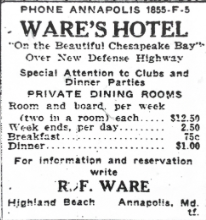

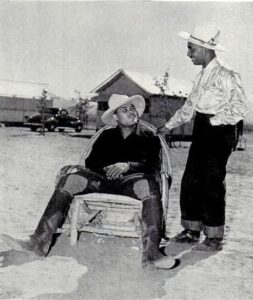

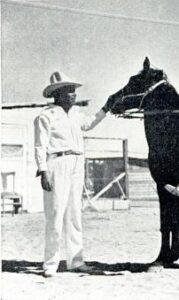

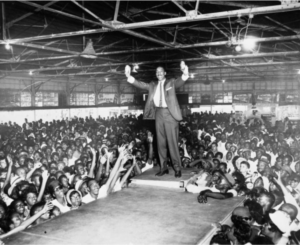

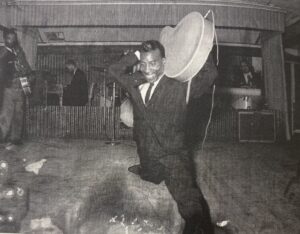

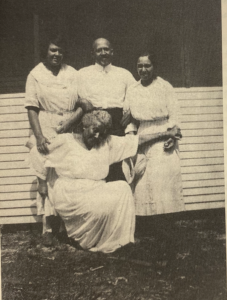

Highland Beach became a vibrant, joy-filled place of leisure for Black families, just as Douglass hoped. His intention was to create a place where “his kind of people” could avoid white harassment. After a few successful seasons and numerous lot acquisitions, the year 1900 saw the emergence of larger, more substantial cottages. Mr. George T. Bowen was among the earliest builders of hotels, followed by the Ware’s Hotel in 1920. The vacation spot was considered the only resort near Washington where they could “derive so much pleasure and solid benefit” from.1 The boating, crabbing, fishing, sailing, sports, dances, parties, and get-togethers were of great attraction. Prominent figures visited the beach, one being Booker T. Washington in August 1908, who stayed at Highland Beach during the National Business League Convention. He enjoyed the features of the Chesapeake Bay and proved himself to be the “best swimmer of the party,” all while visiting his Douglass family friends.2 Highland Beach became the home of a few annual outings. For example, the YWCA summer camp for girls was established in 1931 with dormitories located in the town of Highland Beach. Also during the summer, the American Tennis Association hosted their annual tournaments and the Colored Ministers hosted their annual picnic in the years following.

In the first twenty years, Douglass had already made substantial growth in the area, but unfortunately, he passed in 1920, just before a major development of the beach community. The 1920s ushered in key infrastructural improvements, introducing sewage pipes and electricity that had been previously absent. In 1921, post services were established inside Frederick Douglass’ home, where Audie Lewis became the first postmaster, who then passed the role to Irene Leak in 1922, followed by Fannie Douglass in 1923. Nineteen-twenty-one also marked the formation of the town committee with Chairman Edwin B. Henderson, Haley Douglass (who later became mayor), Eula Ross Grey, Mary C. Terrell, and Milton Francis. After only being established for one year, Governor Albert T. Richie was signing legislation making Highland Beach the first incorporated African American town in Maryland. Soon after, a carekeeper’s house was built in 1938, serving as the town’s only form of a doctor’s office. Not long after, the original carekeepers house was eventually converted into Town Hall, and is still maintained today. The project of building a new pier was taken on in 1950 and completely funded by the inhabitants of the town.

Oral History with Linda Newton, resident of Highland Beach

The town of Highland Beach has completely thrived from the idea of community and protection of one another to provide a place of leisure for those it was not often granted to. The existence of such spaces was critically essential for Black individuals, providing a refuge where they could rest safely, shielded from the oppressive impact of white supremacy on their daily lives. Researching the places that were once used as spaces for leisure not only reminds us of the history, but shows us the importance of rest and peace during eras of hardship. Highland Beach serves as a compelling illustration of how historical narratives unfold visually, told through an array of documents and photographs, and reinforced by its present-day status as a protected historic town.

1 National Endowment for the Humanities, “The Colored American. [Volume] (Washington, D.C.) 1893-19??, September 05, 1903, Pg 3, Image 3,” News about Chronicling America RSS, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

2 National Endowment for the Humanities, “The Washington Bee,” News about Chronicling America RSS, August 29, 1908, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

“Black Soldiers in the Civil War.” National Archives and Records Administration, March 19, 2019. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war/douglass-sons.html

“Charles Remond Douglass.” National Parks Service, March 1, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/nebe/learn/historyculture/charlesdouglass.htm

Fletcher, Patsy Mose. “Sittin’ on the Dock.” Essay. In Historically African American Leisure Destinations around Washington, D.C., 120–77. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2015.

Harrington, NC. “Mary Church Terrell.” FDMCC, November 3, 2022. https://www.fdmcc.org/post/mary-church-terrell

“Highland Beach Notes.” The Colored American, July 13, 1901. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

“Highland Beach Notes.” The Colored American, July 25, 1903. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

Nelson, Jack E., Raymond L. Langston, and Margo Dean Pinson. Highland Beach on the Chesapeake Bay: Maryland’s first African American Incorporated Town. Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company Publishers, 2008.

“Town of Highland Beach Md .” Town of Highland Beach MD. https://www.highlandbeachmd.org/

List of Images

- Home page and cover photo from Highland Beach Historical Collection

- Original map photo from Highland Beach Historical Collection

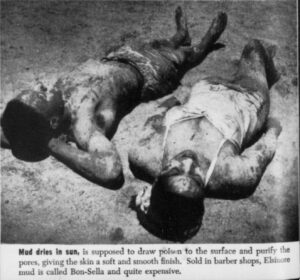

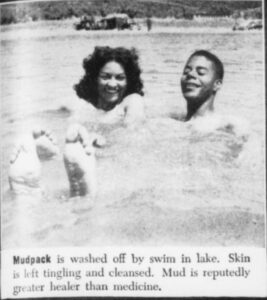

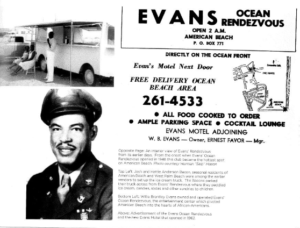

- “Selections from the Collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Earl W. and Amanda Stafford Center for African American Media Arts. Supported by the Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History,” December 1, 2021. https://nmaahc.si.edu/selections-great-migration-home-movie-project

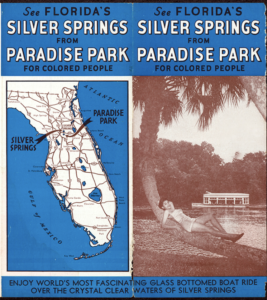

Map thumbnail photos from the Highland Beach Historical Collection

“I have named the place as you will see

‘Highland Beach,’ because the land at

that point is higher than either side

of me on the Beach.”

-Letter from Charles Douglass

to his father, May 15, 1893

“I am down on the Bay spending

the summer. I go out fishing and

crabbing almost every day. I have

learned to swim real well and

I can swim over a hundred

yards without stopping to rest.”

–Haley G. Douglass’

letter to Frederick Douglass

“No such opportunity has ever

before been offered our people to

secure themselves such a desirable

outing site.”

–The Colored American, August 11, 1894